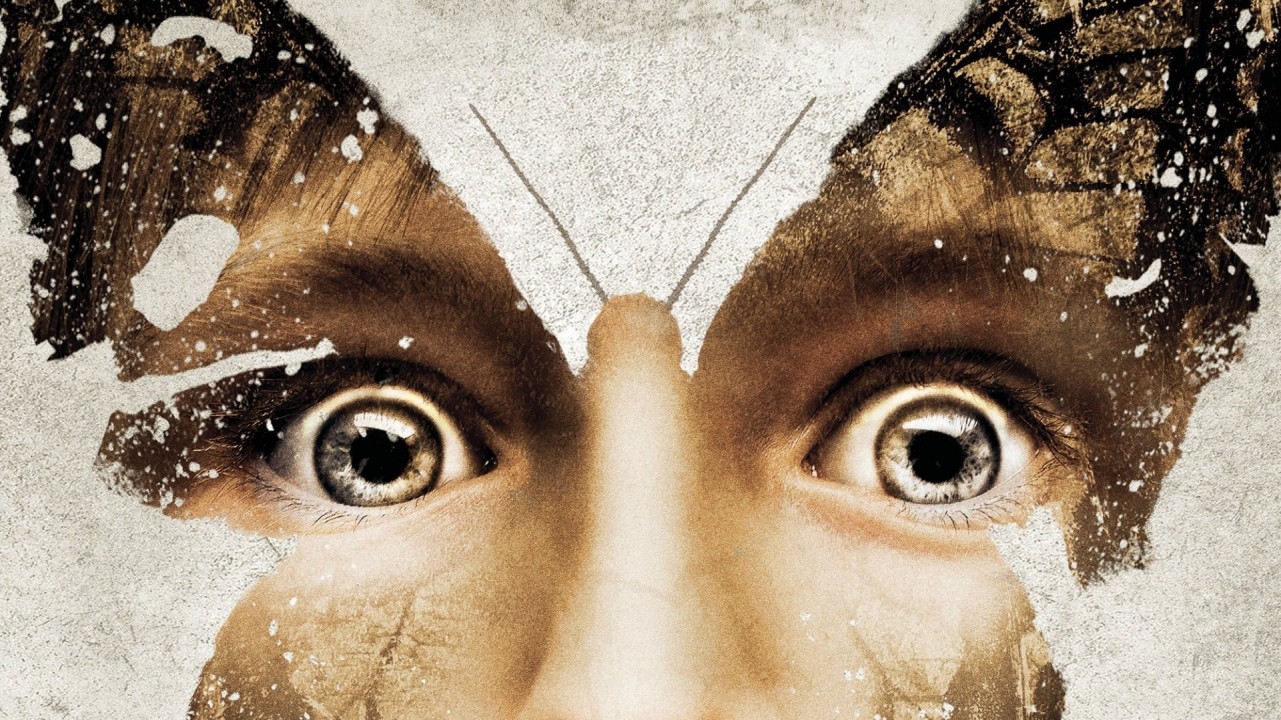

Shots of abandoned homes and underpopulated hospitals abound in empty space and classically expressionist shadows, elegantly elaborating on the loneliness of a splintered family.įlanagan is deeply invested in Cody’s welfare, to the point of rigidly signifying the various manifestations of the boy’s nightmares, pigeonholing irrationality into a rational framework so as to justify a moving yet literal-minded finale. The fakeness of the butterflies, which are obviously CGI, enhances the film’s pathos, reflecting the fragility of Cody’s momentary peacefulness. The butterflies are big and grandly colored, suggesting the product of a gifted child’s imagination and yearning for a transcendence over internal ugliness-such as doubt and guilt-that’s represented here by the desiccated-looking entity that Cody calls the Canker Man (Topher Bousquet).

The images have a pleasing straightforwardness that parallels the openness of Cody’s longing for love.

Cody, so eager to refute his perception of himself as a black sheep, discounts the notion of intimacy, favoring calmer and more stable politeness. When Cody first meets Mark, the young boy extends his hand to his new stepfather, like one might to a person one’s encountering for the first time at a business meeting. Cody’s voice is always accommodating, and seems just a step or two away from cracking. Cody’s desperation to be good, to hold himself to a standard that’s rendered unreachable by his innate gifts-as the film is also a parable of artistic awakening-is intensely poignant.įlanagan often lingers on Tremblay’s face, while the actor elaborates on the tension bubbling up underneath his adorable visage.

A prodigiously subtle young actor, Tremblay allows the audience to see many fine shades of vulnerability and self-loathing in his character, as he did in Lenny Abrahamson’s Room. Though Flanagan lets elements of his horror narrative hang, he fulsomely elaborates on the emotional contours of Cody’s relationship with Jessie and Mark. This resonant and perverse idea (somewhat reminiscent of David Cronenberg’s The Brood) remains untapped, deflating Before I Wake at its midpoint and nearly leaving it without a rudder.īefore I Wake is less a horror film than a metaphorical fantasy in the key of Val Lewton. The issue of Jessie’s exploitation of Cody, which suggests a kind of violation, is dropped almost as soon as it’s broached, as Flanagan can’t bear the idea of watching Cody as he comes to enjoy a loving relationship that might be rooted in an exploitive illusion. Flanagan is one of the horror genre’s few humanists, however, and so he approaches his narrative with a carefulness that’s admirable but also restricting. In this cauldron of neuroses another fear is expressed: an orphan child’s suspicion that his parents’ “real” children are better, closer, and essentially irreplaceable.Ī filmmaker of visionary sadism, such as David Fincher, might have made an alienating and formally rapturous feast of this premise, homing in on the way a family eats itself alive as each member succumbs to obsession. Realizing Cody’s powers, Jessie inundates the boy with pictures and home videos of Sean, so that Sean will appear in Cody’s dreams and re-materialize, briefly “returning” to his parents. Cody is fascinated by butterflies, and so Jessie and Mark see butterflies fluttering around their house as Cody sleeps. In group therapy, Jessie says that she feels as if she can’t awaken following Sean’s death, while Cody suffers from the opposite problem, feeling pressured to avoid sleep, gorging on sugar and caffeine because his dreams assume a physical reality. Throughout Before I Wake, Flanagan links or contrasts Jessie and Cody in a variety of symbolic flourishes. Which is to say that Jessie, Mark, and Cody are all profoundly damaged individuals. Unable to have more children, they adopt eight-year-old Cody (Jacob Tremblay), whom we first see in bed while a previous stepfather looms over him with a pistol. Jessie (Kate Bosworth) and Mark (Thomas Jane) are a couple who lost their child, Sean (Antonio Evan Romero), in a bathtub drowning. This fear is similar to the terror that parents have of inadvertently destroying or disappointing their children, and Flanagan unites these anxieties with a ghoulishly inventive plot turn that he doesn’t fully explore.

Mike Flanagan’s Before I Wake hints-in flashes-at a remarkably cruel psychodrama, physicalizing one of the worst and most common fears that orphans share: that they’re awful and unlovable, and therefore undeserving of parents.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)